Telling the Story: Artists’ Books

Telling the Story: Artists’ Books examines contemporary books in which diverse formats are used. For some, the book form is the primary means of expression, while others, involved with multiple disciplines, treat the book as an extension of their repertoire.

The origin of the book dates back thousands of years. Many artists today have been influenced not only by western approaches to bookmaking, but ancient eastern techniques and materials. It is estimated that books were used as early as 3,000 years ago. Man had the desire to create a record of his experiences and, ultimately, materials were developed allowing these documents, scrolls etc. to be portable. The book of antiquity was considered precious and attributed special status because of the intense labor involved when artists illuminated or illustrated the text. In the East, the first book may have been made of bamboo or palm leaves in the shape of a fan or the blind form, similar in structure to venetian blinds.

The prototype for the book we know today was constructed by the Romans. They used pieces of thin wood treated with heat and wax, binding them together with cord or leather. With the increasing use of paper around 800 AD and, ultimately, the invention of movable type in 1450, books became more accessible. During the Industrial Revolution great strides were made in printing and printmaking, effecting the production of books. The hand-bound or limited edition book resurfaced to mark every major art movement in the twentieth century. Artists’ books seem to proliferate when individual expression and the desire to work outside the traditional confines of painting and sculpture are on the rise.

In 2006, it’s about time we take a close look at the present day art of making books special. This show includes works by thirty-two artists from the Mid-Atlantic region. The artists presented in Telling the Story: Artists’ Books merge text, form and narrative with the visual through handcrafted, sculptural, photographic and technological means. Debra Weier’s pop-up books are architectonic in structure and several refer to concrete poetry, visual notions of human evolution and life and death. The final form of Lai Chung Poon’s autobiographical graphic narrative is a sphere of folded pages based on origami. The process of construction is displayed on a DVD projector. She further expounds upon her life via an audio component. Suzanne Reese Horvitz uses glass as a principle medium for several of her books. Innumerable artists in the exhibit use accordion forms, cut-outs and other variations on traditional Western codex books. The codex book usually has uniform or irregular pages that follow a sequential pattern and is bound on one side by cord, string, leather or board.

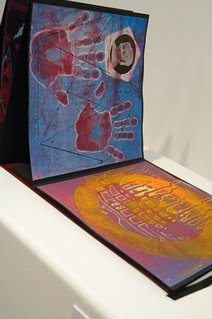

Many of the artists included in this exhibit are concerned with socio-political concepts that underlie means of production. In these works, images and text converge to promote a heightened awareness of issues for social change. Erasure by Curlee Holton broaches the subject of race and the duplicity of consciousness in which a colored face is transformed into a white one. Is this Holton’s commentary on what white America expects of its black masses? Printmaker, Gordon Murray weaves through the image of his prints a political parable that addresses the peril of silence in response to atrocities. Michael Platt and Carol A. Beane’s riveting and haunting visuals and text in Solitary Mornings hint at their African American heritage, yet it is the power of this collaborative work in which one is made to understand reverence for the aged and the need to pour libations in honor of the dead. Joyce Wellman, particularly moved by a conference she attended on the Underground Railroad, devoted a collection of abstracted etchings constructed as an accordion book, to illuminate narratives by ex-slaves, whose stories she presents on DVD. Doug Beube and Zoe Darling’s works hinge on moral issues. While Doug attempts to reconcile the act of repentance in Sin and Repent, indicating symbolically that the memory of sin is ever present, Darling evokes a contemporary assessment of the Roe vs. Wade ruling by the Supreme Court in 1973. This law could possibly become null and void in the near future, thus threatening strides women have made over the past three decades in gaining control over their lives and their bodies.

The categorization of artists’ books is an arena that is open for discourse. Artist/writer/historian, Johanna Drucker has taken the initial steps toward the establishment of a canon. She states that a critical terminology based on an historical perspective and descriptive vocabulary is important to further the discourse on artists’ books. I can appreciate Drucker’s call for a structured approach to assessing artists’ books, but I think that the aesthetician and art historian can apply criteria used to define ideas and concepts related to general art practices. Areas in which additional criteria may be needed are: the creation of the hand bound book as a traditional craft executed by artisans, and the role of publishers in production. A publisher’s influence often impacts the direction a book will take in contrast to artist-driven works.

The point of departure for selecting works for this exhibit had much to do with form and content. The impetus for creation of the works presented focuses on ideas that stem directly from the artist. Preferences leaned toward books that were variations on the codex form and book objects. The definition of the artist book varies, but in many instances multiple approaches, in addition to basic book forms, are employed.

Narrative works based on poems or text generated by the artist are evident in pieces by Shellie Jacobson, MaryAnn Miller, Carol Moore, Liz Mitchell, Robert Roesch and Margot Lovejoy. While Jacobson and Miller’s works are directly related to the imagery evoked by the text, Suzanne Horvitz, Liz Mitchell and Lovejoy’s uses of text are carefully woven into the fabric of the book with collaged revelatory and enigmatic images. Lovejoy in Paradox Mutations contrasts the modernist idealization of concepts such as truth, unity and freedom with images reflective of a fragmented post-modern society, driven by technology. Twin Mirror Image by Horvitz delves into the idea of opposition and the merging of disparate figures and forms drawn or digitally altered. Robert Roesch binds his codex book in aluminum. Sea Sense, devoted to Roesch’s descriptive exploits as a seaman, is contrasted with abstract depictions of geometric forms that hint at the presence of sea and sailboat and the horizon line. Liz’s works punctuate the significance of the narrative, labeling them as “unstoppable stories” in her accordion fold book rough waters/blue skies. The essence of sky and water is evoked in this powdery blue multilayered book of collaged linoleum cut prints with chine collé. Miriam Shaer combines text with a whimsical sculpturally derived form in the work Baby Love. She makes a pun of a lover’s lament by writing the lyrics of this song, made famous by the Supremes, in a bound book with cut out pages in the shape of an infant’s dress. She intentionally alters the words to convey her ambiguity about having children. Carol Moore prints sonnets by obscure Renaissance women on handkerchiefs, which she often incorporates in installations, resurrecting the work of these women for the general public to admire.

Although Lois Morrison uses text, what dominates her works are intricate cut-outs of various characters such as those found in the Land of Shadows and the multi-limed titan from Greek mythology, Geryon. Barton Lidice Benes’ sardonic title American Pie alludes to infamous people in recent American history. Intended to heighten awareness of global warming is Libby Newman’s book. Her visuals are digital prints from wood cuts; she includes poems on this poignant subject by youth from the Interfaith Youth Poetry Project. Miriam Beerman is represented by a journal styled piece. She subtly alludes to the travesties of war and includes excerpts by the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca along with her own personal notations. Her graphic gestural approach to mark-making is punctuated by the intimate scale of the book. Collaborative endeavors are not foreign to the book arts- Robin Rice and Antonio Puri work together to create an accordion book and a scroll. Although language is a part of these works, in the accordion piece it is obfuscated.

Visual books dependent only on the color form and plastic elements on the page are well represented in this exhibit. Karen Guancione creates a diary of found objects, drawings and love notes; E. J. Montgomery’s Spiritual Encounters is designed to suggest the feeling of a journey through nature at different times of the day or year. Debra Weier, inspired by Japanese scrolls, creates a book in which the elements that tie the work together— string and geometric shapes— extend continuously through it. Mystic Traveler is a unique construction by Maryann J. Riker and is about the different twists and turns one takes in life. The snail shells are analogous to the baggage carried in life and how the shell serves as a protective shelter. Riker diverges from the traditional book format, creating a boxed puzzle. Maria Pisano works thematically and her tunnel books on display are based on the four elements. Nyugen Smith’s miniature Carry Book is bound in the remnant of a leather glove and nestled within fur wrappings. This work is made of yellowed parchment paper with random red markings throughout.

At this juncture in a post-conceptualist era, most of the works in this exhibit are concerned with conveying a particular idea outside formal aesthetic concerns. We present a snapshot of the evolution of the artists’ book from limited edition books to the altered appropriated book work. The celebration of the artists’ books by artists, collectors and institutions in America has been growing constantly since the ‘60s. The advent of the Conceptualist movement fostered an anti-establishment approach to making art, capable of operating outside the hegemony of the museum world, in an attempt to make it more democratic. However, according to Lucy Lippard, “Communication (but not community) and distribution (but not accessibility) were inherent in Conceptual art”. If the directive of democratization was not reached, at least, through the years, the artists’ books provided a viable alternative means for expression and social commentary and activism. It has always had the potential to attract audiences beyond the mainstream. The art of the book is alive and flourishing.

The Noyes Museum of Art

All content © 2006 Black Artists of DC all rights reserved.

For permission to reproduce contact: editor@blackartistsofdc.org